Tag: US Sanitary Commission

Wikipedia says: The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) was a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the United States Army (Federal / Northern / Union Army) during the American Civil War.[a] It operated across the North, raised an estimated $25 million in Civil War era revenue (assuming 1865 dollars, $422.66 million in 2021) and in-kind contributions to support the cause, and enlisted thousands of volunteers. The president was Henry Whitney Bellows, and Frederick Law Olmsted acted as executive secretary. It was modeled on the British Sanitary Commission, set up during the Crimean War (1853-1856), and from the British parliamentary report published after the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (“Sepoy Rebellion”).

Henry Whitney Bellows, (1814-1882), a Massachusetts clergyman, planned the USSC and served as its only president.[c] According to The Wall Street Journal, “its first executive secretary was Frederick Law Olmsted, (1822-1903), the famed landscape architect who designed New York’s Central Park”. George Templeton Strong, (1820-1875), New York lawyer and diarist, helped found the commission and served as treasurer and member of the executive committee.

In June 1861, the Sanitary Commission set up its central office inside the United States Treasury Building, just east of the Executive Mansion (now the White House), on Pennsylvania Avenue and 15th Street in central Washington, D.C. By late October 1861, the USSC Central Office and the U.S. War Department had received detailed studies and reports from the Sanitary Inspectors of more than four hundred regimental camp inspections. The rapidly crowded events of those first six months of the war displayed the sheer gravity of the situation in which the adjustment to the means and agencies were desperately needed to ensure a high health-rate in all those untrained Union Army regiments.

Immediately following the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, the first orders and receipts submitted to the Central Office began to arrive from the military Union Army hospitals at Alexandria, Virginia, and Washington, D.C., requesting water-beds, small tables for writing in bed, iron wire cradles for protecting wounded limbs, dominoes, checkerboards, Delphinium and hospital gowns for the wounded.

The demands of the war soon required more frequent decision-making. This led to the creation of the Standing Committee, which met on a nearly daily basis in New York City where most of its members resided. The Standing Committee initially consisted of five commissioners who retained their position for the entire war: Henry W. Bellows, George Templeton Strong, William H. Van Buren, M.D., Cornelius R. Agnew, M.D., and Wolcott Gibbs, M.D.

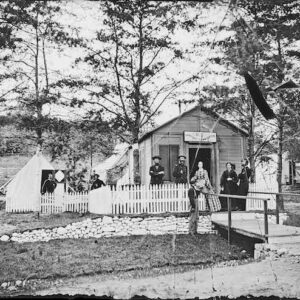

In addition to setting up and staffing hospitals, the USSC operated 30 soldiers’ homes, lodges, or rest houses for traveling or disabled Union soldiers. Most of these closed shortly after the war.

Also active in the association was Colonel Leavitt Hunt, (1831-1907), a New York lawyer and pioneering photographer. In January 1864, he wrote to 16th President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary John George Nicolay asking that Nicolay forward him any documents he might have available with the President’s signature. Hunt’s mother, the widow of Vermont congressman Jonathan Hunt, planned to attach Lincoln’s signature to copies of several casts of the President’s hand, to be sold to raise funds for the war effort. Other fund raising events included the famous 50 pound sack of flour that was auctioned off by Reuel Colt Gridley. By auctioning off the same sack of flour, which was then re-donated to be sold again, Gridley eventually raised more than $250,000.00 for the Sanitary Commission.

States could use their own tax money to supplement the Commission’s work, as Ohio did. Under the energetic leadership of Governor David Tod, a War Democrat who won office on a coalition “Union Party” ticket with Republicans, Ohio acted vigorously. Following the unexpected carnage at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862, it sent three steamboats to the scene as floating hospitals with doctors, nurses and medical supplies. The state fleet expanded to eleven hospital ships. The state also set up 12 local offices in main transportation nodes to help Ohio soldiers moving back and forth.

The government constructed the Pension Building in Washington, DC to handle all the staff to process the pension requests and administer them. It is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. After the war, the USSC volunteers continued to work with Union Army veterans to secure their bounties, back pay, and apply for pensions. It supported the “health and hygiene” of the veterans. They had a Department of General Relief which accepted donations for veterans, too. The USSC organization was finally disbanded in May 1866.

Women in the USSC

Arising from a meeting in New York City of the Women’s Central Relief Association of New York, the organization was also inspired by the British Sanitary Commission of the Crimean War. The American volunteers raised money (estimated at $25 million), collected donations, made uniforms, worked as nurses, ran kitchens in army camps, and administered hospital ships, soldiers’ homes, lodges, and rests for traveling or disabled soldiers. They organized Sanitary Fairs in numerous cities to support the Federal army with funds and supplies, and to raise funds for the work of the USSC. Women who were prominent in the organization, often traveling great distances, and working in harsh conditions, included Louisa May Alcott, Almira Fales, Eliza Emily Chappell Porter, Katherine Prescott Wormeley, and many others.

Dorothea Dix, serving as the commission’s superintendent, convinced the medical corps of the value of women working in their hospitals. Over 15,000 women volunteered to work in hospitals, usually in nursing care. They assisted surgeons during procedures, gave medicines, supervised the feedings and cleaned the bedding and clothes. They gave good cheer, wrote letters the men dictated, and comforted the dying. A representative nurse was Helen L. Gilson (1835–68) of Chelsea, Massachusetts, who served in Sanitary Commission. She supervised supplies, dressed wounds, and cooked special foods for patients on a limited diet. She worked in hospitals after the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg. She was a successful administrator, especially at the hospital for black soldiers at City Point, Virginia. The middle-class women who volunteered provided vitally needed nursing services and were rewarded with a sense of patriotism and civic duty in addition to the opportunity to demonstrate their skills and gain new ones, while receiving wages and sharing the hardships of the men.

Mary Livermore, Mary Ann Bickerdyke, and Annie Wittenmeyer played leadership roles. After the war some nurses wrote memoirs of their experiences; examples include Dix, Livermore, Sarah Palmer Young, and Sarah Emma Edmonds. Bridget Diver also worked for the Commission.

Sanitary Fairs

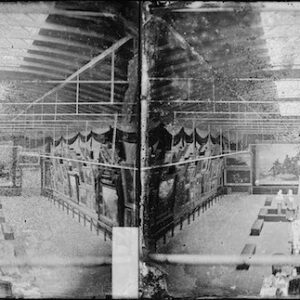

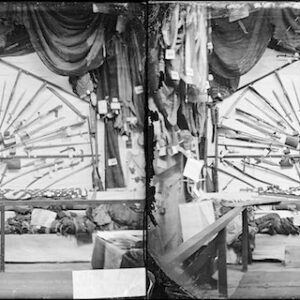

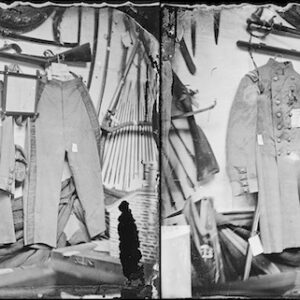

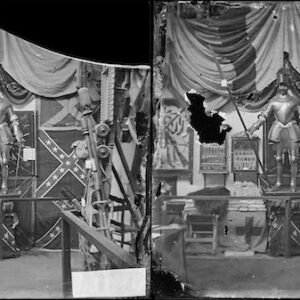

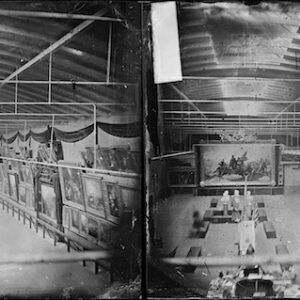

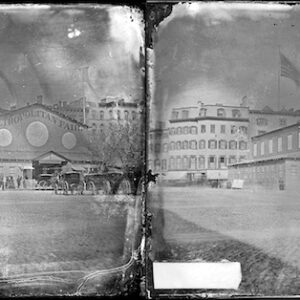

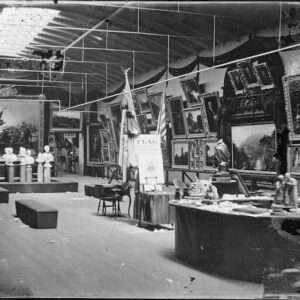

From the outset, many local groups sponsored fund-raising events to benefit the Commission. As the war progressed these became larger and more elaborate. In February 1863, the women of Lowell, Massachusetts, organized a two-day “Mammoth Fair” occupying two exhibition halls and netting over four thousand dollars for the cause. Groups in other cities soon adopted this plan. Organizing these Sanitary Fairs offered ways for local communities to be directly part of supporting the war effort of the nation. The largest Sanitary Fair during the war was held in Chicago from October 27 to November 7, 1863. Called the Northwestern Soldiers’ Fair, it raised almost $100,000 for the war effort. It included a six-mile-long parade of militiamen, bands, political leaders, delegations from various local organizations, and a contingent of farmers, who presented carts full of their crops. Chicago’s Northwestern Soldiers’ Fair included a “Curiosity Shop” of war souvenirs and Americana. Its organizers intended its displays of weapons, slavery artifacts and other items to illustrate for Union visitors the contrast between the “barbaric” Southern enemy and the “civilized” North. The fairs generally involved large-scale exhibitions, including displays of art, mechanical technology, and period rooms. These sorts of displays called upon ideas of the American past, a history that local communities held in common. Often, different communities competed with each other over their donations to the national cause. People in various cities and towns across the North contributed to the same war effort because they identified as having shared fortunes in their common nation.

The USSC leadership sometimes did not approve of the excitement and lavishness of the fairs. They wanted to encourage sacrifice as a component of membership in a nation. Although the fairs were one way to create a national identity which might motivate citizens to perform their duties, the commission leadership did not want the fairs to become the focus of USSC work.

Chicago held a second sanitary fair from April 27, 1865 to June 21, 1865 and the women organizers published a newspaper entitled Voice of the Fair that was distributed at the event.

Notable members

Louisa May Alcott served as a nurse for the Sanitary Commission at a Union Army Hospital in Georgetown.

Mary Ann Bickerdyke served as a nurse for the Sanitary Commission and is credited with establishing 300 field hospitals during the Civil War.

Henry Whitney Bellows served as the President of the Commission.

Atherton Blight, served as a Director of the Commission.

Samuel Howe served as a Director of the Commission.

Mary Livermore led the Northwestern Branch of the Sanitary Commission

John Strong Newberry

Frederick Law Olmsted served as the Executive Secretary of the Sanitary Commission.

George Templeton Strong was Treasurer of the Commission

Showing 1–16 of 58 results

-

Image ID: ABGX

$4.99 -

Image ID: ABJQ

$6.99 -

Image ID: ACJQ

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: ACVE

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVG

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVJ

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVL

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVO

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVU

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACVW

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACWH

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACWK

$3.99 -

Image ID: ACYS

$4.99 -

Image ID: ACYV

$4.99 -

Image ID: ADHU

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: AEJT

$3.99