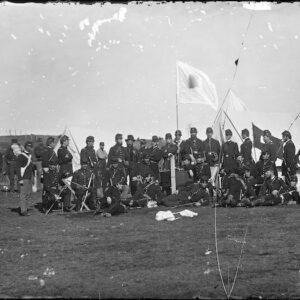

Tag: Signal Corps

Wikipedia says: The Signal Corps in the American Civil War comprised two organizations: the U.S. Army Signal Corps, which began with the appointment of Major Albert J. Myer as its first signal officer just before the war and remains an entity to this day, and the Confederate States Army Signal Corps, a much smaller group of officers and men, using similar organizations and techniques as their Union opponents. Both accomplished tactical and strategic communications for the warring armies, including electromagnetic telegraphy and aerial telegraphy (“wig-wag” signaling). Although both services had an implicit mission of battlefield observation, intelligence gathering, and artillery fire direction from their elevated signal stations, the Confederate Signal Corps also included an explicit espionage function.

The Union Signal Corps, although effective on the battlefield, suffered from political disputes in Washington, D.C., particularly in its rivalry with the civilian-led U.S. Military Telegraph Corps. Myer was relieved of his duties as chief signal officer by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton for his attempts to control all electromagnetic telegraphy within the Signal Corps. He was not restored to his role as chief signal officer until after the war.

The “father” of the U.S. Army Signal Corps was Major Albert J. Myer, an Army surgeon with an interest in communications by sign language for the deaf and then in signaling over long distances with lightweight and simple to use equipment. He invented a signaling system using a flag (or a kerosene torch for nighttime use) that is known as wig-wag signaling, or aerial telegraphy. Unlike semaphore flag signaling, which employed two flags, signal wig-wag required only one, using a binary code to represent each letter of the alphabet or digit. Myer was serving at Fort Duncan, Texas, in 1856 when he wrote to Secretary of War Jefferson Davis and offered his signaling system to the War Department. Although the chief engineer of the Army, Colonel Joseph G. Totten, supported Myer’s proposal, it did not include specific technical details and Davis rejected it. When John B. Floyd replaced Davis as secretary of war in 1857, Totten reintroduced Myer’s proposal, and in March 1859, a board of examination was formed in Washington, D.C. The board, presided over by Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, was not enthusiastic about the proposal, judging it suitable only as a secondary means of communications over short distances, but it did recommend further testing.

Myer began testing in April 1859 at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and then New York Harbor, West Point, New York, and Washington, D.C. One of Myer’s principal assistants was Second Lieutenant Edward Porter Alexander, the future Confederate signal, engineer, and artillery officer. They were able to communicate at distances up to 15 miles and Myer reported to the War Department that the tests had “exceeded anticipation.” He recommended that the Army adopt his signaling system and that he should be placed in charge of it.

On March 29, 1860, the United States House of Representatives approved the Army appropriations bill for fiscal year 1861, which included the following amendment:

For the manufacture or purchase of apparatus and equipment for field signals, $2000; and that there be added to the staff of the Army one signal officer, with the rank, pay, and allowance of a major of cavalry, who shall have charge, under the direction of the Secretary of War, of all signal duty, and all books, papers, and apparatus connected therewith.

The United States Senate eventually approved the appropriations bill, over the objections of Jefferson Davis, now Senator from Mississippi, and President James Buchanan signed it into law on June 21, 1860, the date now celebrated as the birthday of the modern U.S. Army Signal Corps. Myer’s appointment as the first signal officer with the rank of major was confirmed by the Senate on June 27. However, the appropriations bill provided for no personnel to work for Myer and the Signal Corps as a formal organization would not be authorized until March 1863.

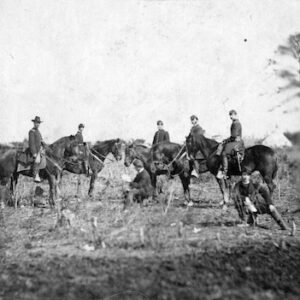

Immediately before the war, Myer was assigned to the Department of New Mexico to test his signals in the field during a campaign against the Navajos. In that assignment, he was assisted by Second Lieutenant William J. L. Nicodemus, who would later succeed him as chief signal officer. Field testing proceeded successfully, and won the admiration of Major Edward Canby, who became a strong advocate of forming a dedicated Signal Corps; Myer at this time believed that the best approach for staffing signal work would be to train officers across the Army in its disciplines.

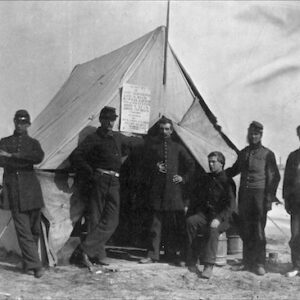

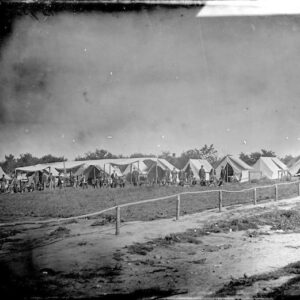

War organization

Upon the outbreak of war, Myer returned to Washington and addressed the problem of having no signal personnel. His only option was to persuade officers to be detailed from other assignments, which was not considered satisfactory by Myer or the officers themselves, who feared loss of promotion opportunities. He submitted draft legislation to Secretary of War Simon Cameron in August 1861, proposing that a Signal Corps be established with himself, seven assistant signal officers, 40 warrant officers, and 40 signal artificers to serve as line builders and repairmen. He intended that each division of the Army, which he assumed would eventually comprise 500,000 men, would have dedicated aerial and electromagnetic telegraphy support. Congress adjourned without considering the legislation. That fall, Myer, who in addition to being chief signal officer for the Army, served as chief signal officer of the newly formed Army of the Potomac, set up training facilities for detailed officers and men in Fort Monroe and at Red Hill, Georgetown, Washington, D.C. His latter training camp remained in operation through the Peninsula Campaign and the rest of 1862, a period in which he continued to lobby with Congress and the Secretary of War, now Edwin M. Stanton, to establish a permanent corps.

Myer’s persistence paid off when President Abraham Lincoln signed a sundry civil appropriations bill on March 3, 1863, which authorized the organization of a Signal Corps during the “present rebellion.” It included the position of chief signal officer with the rank of colonel, a lieutenant colonel, two majors, a captain for each corps or military department, and as many lieutenants, not to exceed eight, per corps or department as the president deemed necessary. Each officer was provided one sergeant and six privates. Myer was appointed to the position of chief signal officer and the rank of colonel by Secretary Stanton on April 29, but his appointment could not be immediately confirmed by the Senate, which was in recess.

Although Myer interpreted his appointment to include control over electromagnetic telegraphy, a rival organization emerged. The U.S. Military Telegraph Corps employed civilian telegraph operators, with supervisors who received military commissions in the Quartermaster Department, under the general management of Anson Stager, a former official of the Western Union Telegraph Company. In February 1862, Lincoln took control of the nation’s commercial telegraph lines, which were then used by Stager’s organization. Secretary Stanton, a former director and attorney for the Atlantic and Ohio Telegraph Company, understood the technical and strategic importance of telegraphy and located the telegraph office directly next to his own in the War Department. One of his biographers described the operators as Stanton’s “little army … part of his own personal and confidential staff.” Myer began a campaign to supersede this organization by proposing the purchase of equipment to form telegraph trains (in the sense of wagon trains, not railroad) in the Signal Corps, to provide mobility for telegraph operators supporting armies on the move. Since he was concerned about the training required for telegraph operators using traditional Morse key equipment, he outfitted his trains with a magneto-electric telegraph instrument invented by George W. Beardslee of New York City. When this device suffered from technical limitations, in the autumn of 1862 he advertised in the Army and Navy Official Gazette for trained telegraphers. The War Department informed Myer that his actions were “irregular and improper” and he was removed as chief signal officer on November 10, 1863. All of the Beardslee devices were given to the Military Telegraph Service (which never used them, due to unreliability) and Myer was transferred to Memphis, Tennessee. His replacement as acting chief signal officer was Major William J. L. Nicodemus, his former apprentice. During his exile in the West, Myer’s A Manual of Signals: For the Use of Signal Officers in the Field was published in 1864, a work that would remain the basis of signal doctrine for many years.

Nicodemus inherited an organization that had grown to approximately 200 officers and 1000 enlisted men. He also ran afoul of Secretary Stanton when the 1864 annual report for the Signal Corps was published because it revealed that the corps was able to read the enemy’s signals. Stanton rightfully believed this to be a breach of security and he dismissed Nicodemus from the Army in December 1864. The final chief signal officer during the war was Colonel Benjamin F. Fisher, former chief signal officer of the Army of the Potomac, who had been captured near Aldie, Virginia, in the Gettysburg Campaign and spent eight months in Libby Prison before escaping and returning to duty.

The Signal Corps completed its wartime service and was dissolved in August 1865. During its lifetime, 146 officers were commissioned in the corps or were offered commissions. There were 297 acting signal officers appointed, although some were for very brief periods. The total number of enlisted men who served during the war was about 2,500.

Albert Myer was eventually rescued from oblivion. In May 1864, Myer’s prewar ally, Edward Canby, selected him to be the signal officer for the Military Division of West Mississippi. Myer served in this position as a major because his confirmation as a colonel had been revoked after his dismissal from Washington. At the end of the Civil War, he was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general. On July 28, 1866, reacting to the influence of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and President Andrew Johnson, Congress reorganized the Signal Corps and, with the permanent rank of colonel, Myer again became chief signal officer, as of October 30, 1866. His new duties included control of the telegraph service, resolving the dispute that had removed him from his position.

Showing all 12 results