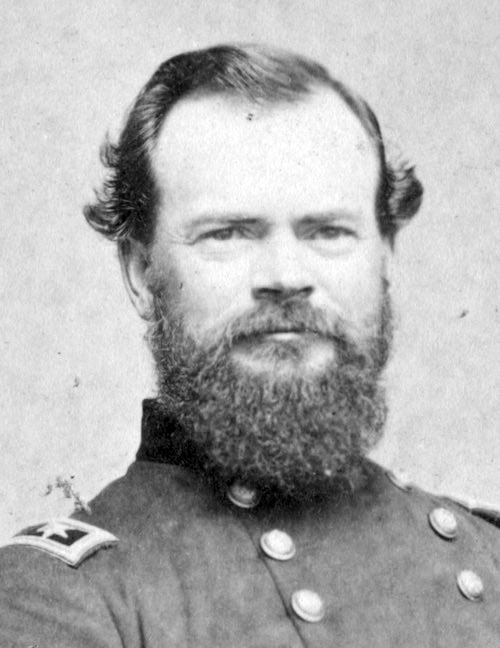

Tag: McPherson (James B.)

Wikipedia says: James Birdseye McPherson (November 14, 1828 – July 22, 1864) was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed at the Battle of Atlanta, facing the army of his old West Point classmate John Bell Hood, who paid a warm tribute to his character. He was the second highest ranking Union officer killed during the war….At the start of the American Civil War, McPherson was stationed in San Francisco, California, but requested a transfer to the Corps of Engineers, rightly thinking that a transfer to the East would further his career. He departed California on August 1, 1861, and arrived soon after in New York. He requested a position on the staff of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, one of the senior Western commanders. He received this (while a captain in the Corps of Engineers), and was sent to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1861, he was made captain, serving under Maj.-Gen. Henry Halleck. Halleck appointed him to the command of the Department of the West in November, where he was chosen aide-de-camp to Halleck while also being promoted to lieutenant-colonel.

Wikipedia says: James Birdseye McPherson (November 14, 1828 – July 22, 1864) was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was killed at the Battle of Atlanta, facing the army of his old West Point classmate John Bell Hood, who paid a warm tribute to his character. He was the second highest ranking Union officer killed during the war….At the start of the American Civil War, McPherson was stationed in San Francisco, California, but requested a transfer to the Corps of Engineers, rightly thinking that a transfer to the East would further his career. He departed California on August 1, 1861, and arrived soon after in New York. He requested a position on the staff of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, one of the senior Western commanders. He received this (while a captain in the Corps of Engineers), and was sent to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1861, he was made captain, serving under Maj.-Gen. Henry Halleck. Halleck appointed him to the command of the Department of the West in November, where he was chosen aide-de-camp to Halleck while also being promoted to lieutenant-colonel.

McPherson’s career began rising after this assignment. He was a lieutenant colonel and the Chief Engineer in Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army during the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862.

During the days that led up to the Battle of Shiloh, McPherson accompanied Sherman questioning people in the area and learned that the confederates were bringing large numbers of troops from every direction by train to Corinth, Mississippi, which was itself an important railroad junction.

Following the Battle of Shiloh, which lasted from April 6–7, he was promoted to brigadier general. On October 8 he was promoted to major general, and was soon after given command of the XVII Corps in Grant’s Army of the Tennessee.

In September 1862, McPherson assumed a position on the staff of General Grant. For his bravery at Corinth he was promoted to major-general, dating from October 8, rising to that position solely on merit. Immediately after the siege of Vicksburg in which McPherson commanded the center, on Grant’s recommendation McPherson was confirmed a brigadier general in the regular army, dating from August 1, 1863. Soon after this promotion, McPherson led a column of infantry into Mississippi and repulsed the enemy at Canton.

On March 12, 1864, he was given command of the Army of the Tennessee, after its former commander, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, was promoted to command of all armies in the West. He then requested leave to go home and marry his fiancé Emily Hoffman in Baltimore, Maryland. His leave was initially granted, but quickly revoked by Sherman, who explained McPherson was needed for his upcoming Atlanta Campaign. McPherson’s army was the Right Wing of Sherman’s army, alongside the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Ohio.

Sherman planned to have the bulk of his forces feint toward Dalton, Georgia, while McPherson would bear the brunt of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s attack, and attempt to trap them. However, the Confederate forces eventually escaped, and Sherman blamed McPherson (for being “slow”), although it was mainly faulty planning on Sherman’s part that led to the escape. McPherson’s troops followed the Confederates “vigorously”, and were resupplied at Kingston, Georgia. The troops drew near Pumpkinvine Creek, where they attacked and drove the Confederates from Dallas, Georgia, even before Sherman’s order to do so. Johnston and Sherman maneuvered against each other, until the Union tactical defeat at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. McPherson then tried a flanking maneuver at the Battle of Marietta, but that failed as well.

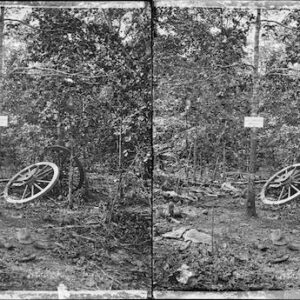

Confederate President Jefferson Davis became frustrated with Johnston’s strategy of maneuver and retreat, and on July 17 replaced him with Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood. With the Union armies closing in on Atlanta, Hood first attacked George Henry Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland north of the city on July 20, at Peachtree Creek, hoping to drive Thomas back before other forces could come to his aid. The attack failed. Then Hood’s cavalry reported that the left flank of McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, east of Atlanta, was unprotected. Hood visualized a glorious replay of Jackson’s famous flank attack at Chancellorsville and ordered a new attack. McPherson had advanced his troops into Decatur, Georgia, and from there, they moved onto high ground on Bald Hill overlooking Atlanta. Sherman believed that the Confederates had been defeated and were evacuating; however, McPherson rightly believed that they were moving to attack the Union left and rear. On July 22, while they were discussing this new development, however, four Confederate divisions under Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee flanked Union Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge’s XVI Corps. While McPherson was riding his horse toward his old XVII Corps, a line of Confederate skirmishers appeared, yelling “Halt!”. McPherson raised his hand to his head as if to remove his hat, but suddenly wheeled his horse, attempting to escape. The Confederates opened fire and mortally wounded McPherson in the back. When the Confederate troops approached and asked his orderly who the downed officer was, the aide replied “Sir, it is General McPherson. You have killed the best man in our army.” This was early in the one-day Battle of Atlanta, part of the Atlanta Campaign that led to the surrender of Atlanta a month later. General Otis Howard succeeded him as commander of the Army and Department of the Tennessee.

His adversary, John Bell Hood, wrote,

I will record the death of my classmate and boyhood friend, General James B. McPherson, the announcement of which caused me sincere sorrow. Since we had graduated in 1853, and had each been ordered off on duty in different directions, it has not been our fortune to meet. Neither the years nor the difference of sentiment that had led us to range ourselves on opposite sides in the war had lessened my friendship; indeed the attachment formed in early youth was strengthened by my admiration and gratitude for his conduct toward our people in the vicinity of Vicksburg. His considerate and kind treatment of them stood in bright contrast to the course pursued by many Federal officers.

When Sherman received word of McPherson’s death, he openly wept. He then penned a letter to Emily Hoffman in Baltimore, stating:

My Dear Young Lady, A letter from your Mother to General Barry on my Staff reminds me that I owe you heartfelt sympathy and a sacred duty of recording the fame of one of our Country’s brightest and most glorious Characters. I yield to none on Earth but yourself the right to excel me in lamentations for our Dead Hero. Why should death’s darts reach the young and brilliant instead of older men who could better have been spared?

McPherson was the second-highest-ranking Union officer to be killed in action during the war (the highest ranking was John Sedgwick). Emily Hoffman never recovered from his death, living a quiet and lonely life until her death in 1891.