Tag: Deep Bottom VA

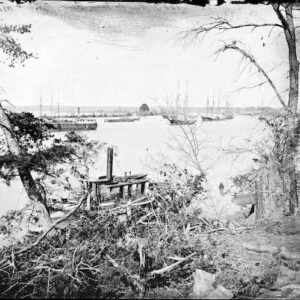

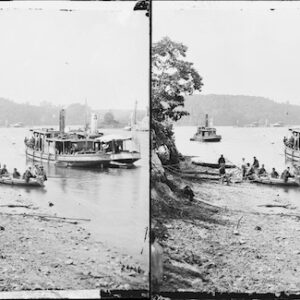

Wikipedia says: Deep Bottom is the colloquial name for an area of the James River in Henrico County 11 miles (18 km) southeast of Richmond, Virginia, at a horseshoe-shaped bend in the river known as Jones Neck. It was a convenient crossing point from the Bermuda Hundred area on the south side of the river.

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant began a siege of the city of Petersburg, Virginia, after initial assaults on the Confederate lines, June 15–18, 1864, failed to break through. While Union cavalry conducted the Wilson-Kautz Raid (June 22 – July 1) in an attempt to cut the railroad lines leading into Petersburg, Grant and his generals planned a renewed assault on the Petersburg fortifications, an attack scheduled for July 30 that would become known as the Battle of the Crater. Hoping to increase the chances for success at Petersburg, Grant planned a movement against Richmond that Gen. Robert E. Lee would likely counter with troops taken out of the Petersburg line.

Grant ordered the II Corps of the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, and two divisions of Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s Cavalry Corps to cross the river to Deep Bottom by pontoon bridge and advance against the Confederate capital. A division of the X Corps (Army of the James), commanded by Brig. Gen. Robert S. Foster, had previously crossed on a second pontoon bridge just upstream to secure a bridgehead on the north bank of the river. Grant’s plan called for Hancock to pin down the Confederates at Chaffin’s Bluff and prevent reinforcements from opposing Sheridan’s cavalry, which would attack Richmond if practicable. If not—a circumstance Grant considered more likely—Sheridan was ordered to ride around the city to the north and west and cut the Virginia Central Railroad, which was supplying Richmond from the Shenandoah Valley.

The Confederate fieldworks protecting Richmond were commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. When Lee found out about Hancock’s pending movement, he ordered that the Richmond lines be reinforced to 16,500 men. The four brigades of Maj. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s division joined Col. John S. Fulton’s brigade of the Department of Richmond and the brigades of Brig. Gens. James H. Lane and Samuel McGowan from Maj. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s division. The reinforcements moved east on New Market Road (present-day Virginia State Route 5) and took up positions on the eastern face of New Market Heights.

The Second Battle of Deep Bottom, also known as Fussell’s Mill (particularly in the South), New Market Road, Bailey’s Creek, Charles City Road, or White’s Tavern was fought August 14–20, 1864, at Deep Bottom in Henrico County, Virginia, during the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign (Siege of Petersburg) of the American Civil War.

During the night of August 13–14, a force under the command of Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock crossed the James River at Deep Bottom to threaten Richmond and attract Confederate forces away from the Petersburg, Virginia, trenches and the Shenandoah Valley. On August 14, the X Corps closed on New Market Heights while the II Corps extended the Federal line to the right along Bailey’s Creek. During the night, the X Corps was moved to the right flank of the Union line near Fussell’s Mill. On August 16, Union assaults near the mill were initially successful, but Confederate counterattacks drove the Federals back. After days of indecisive skirmishing, the Federals returned to the south side of the James on the night of August 20. The Confederates achieved their objective of driving back the Union threat, but at a cost of diluting their forces as the Union had hoped.

In the First Battle of Deep Bottom, July 27–29, Grant sent a force under Maj. Gens. Winfield S. Hancock and Philip H. Sheridan on an expedition threatening Richmond and its railroads, intending to attract Confederate troops away from the Petersburg defensive line. The Union infantry and cavalry force was unable to break through the Confederate fortifications at Bailey’s Creek and Fussell’s Mill and was withdrawn, but it achieved its desired effect of momentarily reducing Confederate strength at Petersburg. The planned attack on the fortifications went ahead on July 30, but the resulting Battle of the Crater was an embarrassing Union defeat, a fiasco of mismanaged resources by Grant’s subordinates at a heavy cost in casualties.

On the same day the Union failed at the Crater, Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early was burning the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, as he operated out of the Shenandoah Valley, threatening towns in Maryland and Pennsylvania, as well as the District of Columbia. Gen. Robert E. Lee was concerned about actions that Grant might take against Early, and in fact Grant in the first week of August designated Phil Sheridan to command a consolidated Army of the Shenandoah to challenge Early with almost 40,000 men. Lee sent the infantry division of Maj. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw from Lt. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s corps and the cavalry division commanded by Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to Culpeper, Virginia, where they could either provide aid to Early or be recalled to the Richmond-Petersburg front as needed. Grant misinterpreted this movement and assumed that Anderson’s entire corps had been removed from the vicinity of Richmond, leaving only about 8,500 men north of the James River. He determined to try again with an advance toward the Confederate capital. This would either prevent reinforcements from aiding Early or once again dilute the Confederate strength in the defensive lines around Petersburg.

Once again, Hancock would be the senior general on the expedition. On August 13, the X Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. David B. Birney, Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg’s cavalry division, and Hancock’s II Corps artillery crossed pontoon bridges from Bermuda Hundred to Deep Bottom. Meanwhile, the remainder of the II Corps conducted a ruse to make the Confederates think that Hancock was being sent north to reinforce Sheridan. After a grueling march through oppressive heat to City Point—a march during which a number of the men were felled by heat stroke—they embarked on ships and steamed toward the Chesapeake Bay, many of the individual soldiers unaware of their actual destination. A tugboat followed the flotilla and brought new orders, which caused the transport ships to turn around and deposit the II Corps at Deep Bottom the night of August 13–14. The landings were not managed well and fell behind schedule; Grant’s staff had not arranged for adequate wharves to handle the deep-water steamers.