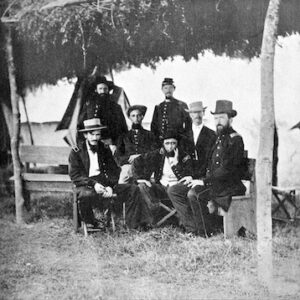

Tag: by Lytle (Andrew D.)

Wikipedia says: Andrew David Lytle (1858–1917) was an itinerant photographer in Cincinnati, Ohio, who worked throughout the mid-South. In 1858, he opened a studio on Main Street in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and for the next half-century recorded the places, events and faces of Louisiana’s capital city. Lytle’s remarkable photograph of the 1st Indiana H.A. is just one of many made in Baton Rouge during its occupation by Union forces. After federal forces occupied Baton Rouge in May 1862, Lytle developed a lucrative photographic relationship with the U.S. Army and Navy. Besides providing studio portraits for members of the occupying forces, Lytle photographed the occupying army encampments around Baton Rouge as well as the Navy’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Admiral James Glasgow Farragut and the Mississippi River Squadron. Many of Lytle’s civil war era works are preserved in the ‘Andrew D. Lytle’s Baton Rouge’ Photograph Collection at Louisiana State University. Lytle’s studio was so successful during the civil war that he was able to buy property with buildings near the Louisiana Governor’s Mansion, which became the Lytle family home for the next sixty years. As Louisiana emerged from Reconstruction, Lytle was joined in the business by his son Howard, operating under the name of Lytle Studio and, later, Lytle & Son.

Wikipedia says: Andrew David Lytle (1858–1917) was an itinerant photographer in Cincinnati, Ohio, who worked throughout the mid-South. In 1858, he opened a studio on Main Street in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and for the next half-century recorded the places, events and faces of Louisiana’s capital city. Lytle’s remarkable photograph of the 1st Indiana H.A. is just one of many made in Baton Rouge during its occupation by Union forces. After federal forces occupied Baton Rouge in May 1862, Lytle developed a lucrative photographic relationship with the U.S. Army and Navy. Besides providing studio portraits for members of the occupying forces, Lytle photographed the occupying army encampments around Baton Rouge as well as the Navy’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron under Admiral James Glasgow Farragut and the Mississippi River Squadron. Many of Lytle’s civil war era works are preserved in the ‘Andrew D. Lytle’s Baton Rouge’ Photograph Collection at Louisiana State University. Lytle’s studio was so successful during the civil war that he was able to buy property with buildings near the Louisiana Governor’s Mansion, which became the Lytle family home for the next sixty years. As Louisiana emerged from Reconstruction, Lytle was joined in the business by his son Howard, operating under the name of Lytle Studio and, later, Lytle & Son.

In 1910 an agent for The Reviews of Reviews Company, New York, publisher of The Photographic History of the Civil War, purchased most of the surviving negatives Baton Rouge photographer Andrew Lytle had created during the Federal occupation of Baton Rouge. The agent also spoke to Howard Lytle about the role his father had played in the war. From that conversation and the subsequent write up in The Photographic History the story of Lytle as “camera spy for the Confederacy” was born. Other than this tale, told fifty years after the fact to a journalist, there is no record any espionage by Lytle. The photographic equipment of the time, including that used by Lytle, involved bulky cameras and large, heavy tripods. The cameras used wet-plate collodion glass-plate negatives with fairly long exposure times. Photographing in the field, a photographer needed a darkroom wagon nearby for preparing the wet plates for exposure and developing them after exposure before they dried. Without a darkroom wagon, a photographer would have required a system of runners or horsemen to relay the wet plates between his studio, the photographic site in the field, and back to his studio.

Showing the single result