Tag: Bermuda Hundred VA

Wikipedia says: Bermuda Hundred was the first administrative division in the English colony of Virginia. It was founded by Sir Thomas Dale in 1613, six years after Jamestown. At the southwestern edge of the confluence of the Appomattox and James Rivers opposite City Point, annexed to Hopewell, Virginia in 1923, Bermuda Hundred was a port town for many years. The terminology “Bermuda Hundred” also included a large area adjacent to the town. In the colonial era, “hundreds” were large developments of many acres, arising from the English term to define an area which would support 100 homesteads. The port at the town of Bermuda Hundred was intended to serve other “hundreds” in addition to Bermuda Hundred.

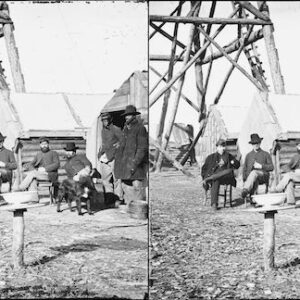

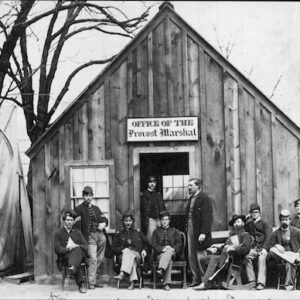

The area of the peninsula between the James and Appomattox Rivers on which Bermuda Hundred is located was part of the Bermuda Hundred Campaign during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

No longer a shipping port, Bermuda Hundred is now a small community in the southeastern portion of Chesterfield County, Virginia.

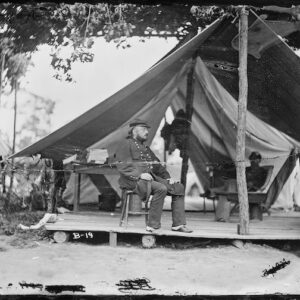

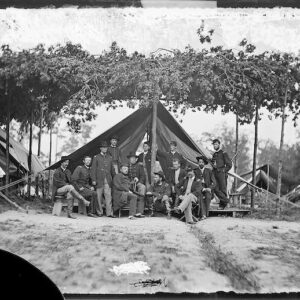

Civil War Period

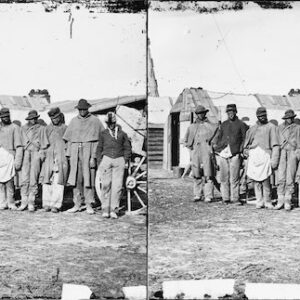

As the Civil War began, the Bermuda Hundred and surrounding countryside had mostly receded into a gracious backwater. Some of the original plantations had fallen into dilapidation and disrepair by the beginning of the war and remained as monuments to a long-ago past when the area was a center of the Virginia economy. Several country estates yet remained in the Bermuda Hundred including, Presquile, Mont Blanco, Rochedale, and Meadowville, as well as nearby Varina, Shirley, Curles Neck, Appomattox, and Weston Manor, the large plantations which continued to dominate the surrounding country life. A number of independent farmers, fresh with prosperity derived from supporting local consumption gained additional income with smaller production of cash crops. Smaller part-time farmers, overseers, and tenant farmers lived in the countryside as well, holding smaller but well built colonial brick homes. Other Virginians, employed as part-time laborers on the farms and plantations and in the larger towns also lived in their own communities in the countryside or town, while the large black population lived a restricted life on the plantations themselves.

Inside the town, the former heady days of merchant adventurers had long become a thing of the past, leaving the merchants more as factors and shipping agents for what remained of the agricultural community. These merchant families, nonetheless earned a prosperous income from trading the highly valued cotton, tobacco and other commercial crops both in the state, in the nation, and internationally thereby keeping an influence and intelligence of world affairs well above what their economic station would presume. Additionally, a community of fishermen continued to work the great Chesapeake Bay, alongside a small class of artisan, craftsmen, boat wrights, and small freight shippers working the traffic along the bay as well as trade further into New England.

The war of independence was still fresh in the memories of these persons. The issues seemed very similar to them and most made valid arguments to the same themes as dominated the Revolutionary debates generations before. Believing that the coming northern Republican Party dominance were threats to the supremacy of the hearth and home, the right of independent yeoman farmer to be supreme in his property, and most importantly, that abolition was being discussed were greeted with consternation. Several families indeed still remained who had served and fought in the war, the grandchildren of their Revolutionary heroes now in command of the debate. Fortune had been sacrificed for their beliefs, and despite the overwhelming odds, the same families pledged their fortunes as well and were loyally greeted as their rightful leaders by the mass of working and farming class Americans in the South.

With the coming of war the area was pressed entirely into the war effort. As the chaos of war spread its way south, and the Union navy put its blockade upon the port, much of the small shipping fleet was captured, destroyed, or lay in disrepair. Those that remained were pressed into being Union blockade runners. Furthermore, a trickle but worrisome number of slaves began escaping. More and more of the white population volunteered into the Confederate Army. Most of the planter class joined the officer corps of the Confederacy, with many killed in the subsequent campaigns. Soon, the old and young were put into defensive work, keeping the countryside clear of escaped slaves and Union raiding parties. Eventually, what remained of the white population was formed into a home guard militia supplemented by veterans from the campaigns in the North as a large Union invading army arrived into the area.

Surviving on a barely prosperous plantation economy, the region was critically damaged in the subsequent Civil War campaigns, principally the Bermuda Hundred Campaign. The Bermuda Hundred Campaign was a series of battles fought in the vicinity of the town during May 1864, in the American Civil War. Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, commanding the Army of the James, threatened Richmond from the east, but was stopped by Confederate forces under Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. The Howlett Line from the James to the Appomattox effectively “bottled up” the northern army on the Bermuda Hundred peninsula. The Campaign was one of the last victories of the Confederacy and General Benjamin Butler was transferred elsewhere.

Showing all 15 results

-

Image ID: ABFC

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: ABMK

$5.99 -

Image ID: ACDP

$4.99 -

Image ID: ACTY

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: ACVN

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: AKTZ

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKUF

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKUY

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKVW

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKVX

$6.99 -

Image ID: AMYM

$1.99 -

Image ID: ANHL

$1.99 -

Image ID: ANJS

$0.99 -

Image ID: AQOP

$6.99 -

Image ID: ASXD

$0.99