Tag: limber

Davis, et. al., Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, plate CLXXIII.

Davis, et. al., Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, plate CLXXIII.

Hazlett, Olmstead and Parks, Field Artillery Weapons of the Civil War says: The limber consists of an axle-body, axle, and two wheels, on which rests a framework to which is attached a tongue. On top of the whole the ammunition chest is secured, mounting with pins and brackets to allow for quickly removing the chest. Two or three cannoneers could ride on the top of the chest.

To counterbalance the weight of the tongue, and thus relieve strain on the horses, the center of gravity is placed slightly to the rear of the center of the axletree.

A long pole or tongue is centered to the chassis, extending forward, and at the front is a pole chain by which the pole is held up, and a yoke with two movable branches to prevent as much as possible the pole from oscillating and striking the horses. Each branch of the yoke has a sliding ring which is connected by a chain to the hames of the horses to allow them greater freedom of motion.

The horses were hitched to the pole by means of a splinter bar with four hooks. A large pintle-hook was mounted at the rear of the chassis with a pin, by which means a gun carriage or a caisson could be pulled–much like the modern trailer hitch.

Inside the cover of the chest was a tray for carrying such things as the gunners’ tools, and a label was pasted to the lid which stated the table of fire.

Wikipedia says: A limber is a two-wheeled cart designed to support the trail of an artillery piece, or the stock of a field carriage such as a caisson or traveling forge, allowing it to be towed. The trail is the hinder end of the stock of a gun-carriage, which rests or slides on the ground when the carriage is unlimbered.

Before the 19th century

As artillery pieces developed trunnions and were placed on carriages featuring two wheels and a trail, a limber was devised. This was a simple cart with a pintle. When the piece was to be towed, it was raised over the limber and then lowered, with the pintle fitting into a hole in the trail. Horses or other draft animals were harnessed in single file to haul the limber. There was no provision for carrying ammunition on the limber, but an ammunition chest was often carried between the two pieces of the trail.

Nineteenth century

The British developed a new system of carriages, which was adopted by the French, then copied from the French by the Americans.

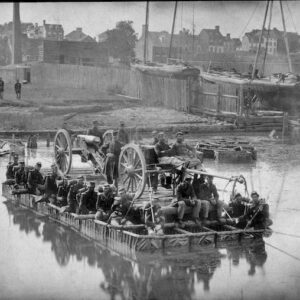

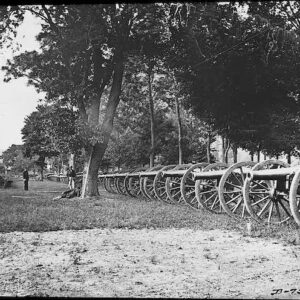

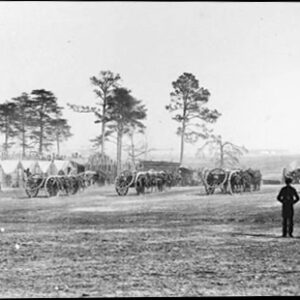

During the American Civil War, U.S. Army equipment was identical to Confederate Army equipment, essentially identical to French equipment, and similar to that of other nations. The field artillery limber assumed its archetypal form – two wheels, an ammunition chest, a pintle hook at the rear, and a central pole with horses harnessed on either side. The artillery piece had an iron ring (lunette) at the end of the trail. To move the piece, the lunette was dropped over the pintle hook (which resembles a modern trailer hitch). The connection was secured by inserting a pintle hook key into the pintle.

The quantity of ammunition in the chest, which could be detached from the limber, depended on the size of the piece. An ammunition chest for the M1857 light 12-pounder gun (“Napoleon”) carried 28 rounds. The cover of the ammunition chest was made of sheet copper to prevent stray embers from setting the chest on fire.

Six horses were the preferred team for a field piece, with four being considered the minimum team. Horses were harnessed in pairs on either side of the limber pole. A driver rode on each left-hand (“near”) horse and held reins for both the horse he rode and the horse to his right (the “off horse”).

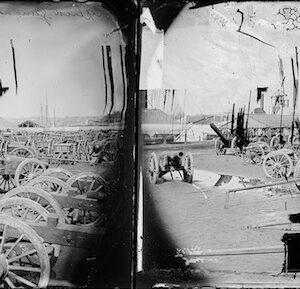

In addition to hauling the artillery piece, the limber also hauled the caisson, a two-wheeled cart that carried two extra ammunition chests, a spare wheel and extra limber pole slung beneath. There was one caisson for each artillery piece in a battery. The cannoneers could ride the ammunition chests on the limbers and the caisson when speed was required, but to do so for any length of time was too tiring for the horses, so cannoneers generally walked. The exception to this rule would be in horse-artillery batteries, where the cannoneers rode saddle horses.

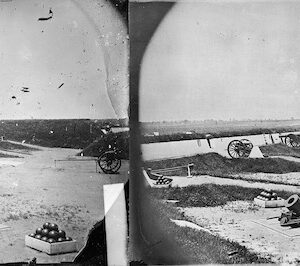

When the artillery piece was in action, the piece’s limber would have been six yards behind the piece, depending on the terrain, with the caisson and its limber farther to the rear of the firing line, preferably behind some natural cover such as a ridge. While firing the piece, if possible, the crew kept the two ammunition chests on the caisson full, preferably supplying the gun from the third ammunition chest on the caisson’s limber. When the ammunition from the ammunition chest on the piece’s limber was exhausted, the piece’s limber and the caisson’s limber exchanged places. The empty ammunition chest was removed, and then the middle chest on the caisson was moved forward onto the limber. A fully loaded ammunition chest for a “Napoleon” 12-pounder weighed 650 pounds, so the chest was dragged and pushed, rather than lifted, into place. With a full ammunition chest in place, the limber was ready to move forward and supply the piece.

Although the limber’s primary purpose was to haul the artillery piece and the caisson, it also hauled the battery wagon and a traveling forge. The battery wagon carried spare parts, paint, etc., while the traveling forge was for use by a blacksmith in keeping the battery’s hardware in repair. The ammunition chest on the limber hauling the battery wagon contained carpenters’ and saddle-makers’ tools, and the ammunition chest on the limber hauling the traveling forge contained blacksmiths’ tools.

Siege artillery limbers, unlike field artillery limbers, did not have an ammunition chest. Siege artillery limbers resembled their predecessors: they were two-wheeled carts with a pintle, now somewhat behind the axle. When the piece was to be hauled, the trail was raised above the limber, then lowered, with the pintle fitting into a hole in the trail. Unlike the situation with its predecessors, horses were harnessed to the 19th-century limber in pairs, with six to ten horses needed to haul a siege gun or howitzer.

Showing 1–16 of 155 results

-

Image ID: AACW

$6.99 -

Image ID: AACZ

$4.99 – $5.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AADG

$6.99 -

Image ID: AAFD

$5.99 -

Image ID: AAFE

$5.99 -

Image ID: AAKL

$3.99 – $4.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AAKO

$4.99 – $6.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AANC

$6.99 -

Image ID: AANS

$4.99 – $5.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AAOJ

$4.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AAOK

$3.99 – $6.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AAPH

$3.99 – $6.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: AATX

-

Image ID: ABDM

$3.99 -

Image ID: ABDS

$3.99 – $6.99 This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Image ID: ABDT

$3.99