Tag: saw

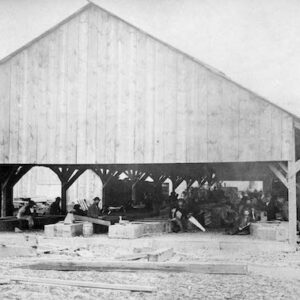

Wikipedia says: A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge. It is used to cut through material, very often wood though sometimes metal or stone. The cut is made by placing the toothed edge against the material and moving it forcefully forth and less forcefully back or continuously forward. This force may be applied by hand, or powered by steam, water, electricity or other power source.

Wikipedia says: A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge. It is used to cut through material, very often wood though sometimes metal or stone. The cut is made by placing the toothed edge against the material and moving it forcefully forth and less forcefully back or continuously forward. This force may be applied by hand, or powered by steam, water, electricity or other power source.

Hand saws typically have a relatively thick blade to make them stiff enough to cut through material. (The pull stroke also reduces the amount of stiffness required.) Thin-bladed handsaws are made stiff enough either by holding them in tension in a frame, or by backing them with a folded strip of steel (formerly iron) or brass (on account of which the latter are called “back saws.”)

Saws were at first serrated materials such as flint, obsidian, sea shells and shark teeth.

In ancient Egypt, open (unframed) saws made of copper are documented as early as the Early Dynastic Period, circa 3,100–2,686 BC. Many copper saws were found in tomb No. 3471 dating to the reign of Djer in the 31st century BC. Saws have been used for cutting a variety of materials, including humans (death by sawing). Models of saws have been found in many contexts throughout Egyptian history. Particularly useful are tomb wall illustrations of carpenters at work that show sizes and the use of different types. Egyptian saws were at first serrated, hardened copper which cut on both pull and push strokes. As the saw developed, teeth were raked to cut only on the pull stroke and set with the teeth projecting only on one side, rather than in the modern fashion with an alternating set. Saws were also made of bronze and later iron. In the Iron Age, frame saws were developed holding the thin blades in tension. The earliest known sawmill is the Roman Hierapolis sawmill from the third century AD and was for sawing stone.

According to Chinese legend, the saw was invented by Lu Ban. In Greek mythology, as recounted by Ovid, Talos, the nephew of Daedalus, invented the saw. In archeological reality, saws date back to prehistory and most probably evolved from Neolithic stone or bone tools. “[T]he identities of the axe, adz, chisel, and saw were clearly established more than 4,000 years ago.”

Once mankind had learned how to use iron, it became the preferred material for saw blades of all kinds; some cultures learned how to harden the surface (“case hardening” or “steeling”), prolonging the blade’s life and sharpness. Steel, made of iron with moderate carbon content and hardened by quenching hot steel in water, was used as early as 1200 BC. By the end of the 17th century European manufacture centred on Germany, (the Bergisches Land) in London, and the Midlands of England. Most blades were made of steel (iron carbonised and re-forged by different methods). In the mid 18th century a superior form of completely melted steel (“crucible cast”) began to be made in Sheffield, England, and this rapidly became the preferred material, due to its hardness, ductility, springiness and ability to take a fine polish. A small saw industry survived in London and Birmingham, but by the 1820s the industry was growing rapidly and increasingly concentrated in Sheffield, which remained the largest centre of production, with over 50% of the nation’s saw makers. The US industry began to overtake it in the last decades of the century, due to superior mechanisation, better marketing, a large domestic market, and the imposition of high tariffs on imports. Highly productive industries continued in Germany and France.

Early European saws were made from a heated sheet of iron or steel, produced by flattening by several men simultaneously hammering on an anvil. After cooling, the teeth were punched out one at a time with a die, the size varying with the size of the saw. The teeth were sharpened with a triangular file of appropriate size, and set with a hammer or a wrest. By the mid 18th century rolling the metal was usual, the power for the rolls being supplied first by water, and increasingly by the early 19th century by steam engines. The industry gradually mechanized all the processes, including the important grinding the saw plate “thin to the back” by a fraction of an inch, which helped the saw to pass through the kerf without binding. The use of steel added the need to harden and temper the saw plate, to grind it flat, to smith it by hand hammering and ensure the springiness and resistance to bending deformity, and finally to polish it. Most hand saws are today entirely made without human intervention, with the steel plate supplied ready rolled to thickness and tensioned before being cut to shape by laser. The teeth are shaped and sharpened by grinding and are flame hardened to obviate (and actually prevent) sharpening once they have become blunt. A large measure of hand finishing remains to this day for quality saws by the very few specialist makers reproducing the 19th century designs.

Showing 1–16 of 17 results

-

Image ID: AABR

$5.99 -

Image ID: AACK

$5.99 -

Image ID: ABGG

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: AFKF

$4.99 – $6.99 -

Image ID: AILP

$6.99 -

Image ID: AJKZ

$1.99 -

Image ID: AKRT

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKRU

$6.99 -

Image ID: AKSW

$6.99 -

Image ID: ALAV

$6.99 -

Image ID: ANMW

$6.99 -

Image ID: ANNB

$6.99 -

Image ID: ANNF

$6.99 -

Image ID: APAD

$6.99 -

Image ID: APUI

$1.99 -

Image ID: AQPL

$6.99